Featured Image: Author’s collection of coloring books. Photograph Betsy Keene, November 2015.

Ever popular among children, coloring books have enjoyed a resurgence of interest as activity for adults. The beloved childhood pastime for quiet moments and rainy days has become a stress-reliever and creative outlet for grown-ups. Yet the coloring book is still a ubiquitous, and inexpensive, childhood toy. Pictured above is my collection of coloring books for children, pictured below is my new (and favorite) coloring book, one of the earliest designed specifically for adults.

Title page of Johanna Basford’s Enchanted Forest: An Inky Quest and Coloring Book (London, UK: Laurence King Publishing, 2015). Colored by Betsy Keene, Fall 2015.

Neither children nor adults wonder about the complicated origins of coloring books. Yet they are one result of important innovations in the printing and publishing industry in the 1800s, changes that resulted in cheaper books, increasing access to readership and literacy, and a wider audience for all kinds of printed material. By the 1890s, books, once an expensive and cherished possession, now a disposable commodity, printed and bound cheaply and called pulps. The earliest coloring books, printed before the age of pulps, were nicely bound and made with quality paper. Their users were instructed to add colors carefully and to keep their work.

As the white American middle class grew, so too did their interest in education, literacy, and childhood. Improvements in quality of life were aided by the reform movements of the late 19th century that sought better circumstances for Americans. Children’s education was valued as a means of social improvement for future generations. Teachers, authors, and education reformers recognized that illustrations were an excellent means of raising a child’s interest in reading.

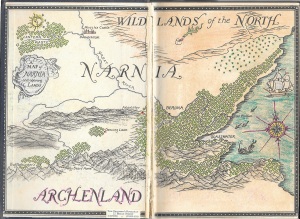

At the same time, water colors, pastels, and wax drawing sticks became common in many households. Given the penchant of all children for scribbling on any available paper (regardless of whether or not they should), it was a logical step to print images specifically for that purpose. But evidence survives of children coloring in books never intended for the purpose. Pictured below is the map in a signed copy of C.S. Lewis’ Prince Caspian, which the author’s aunt colored as a child in the early 1960s, considerably devaluing the book. This behavior is seen commonly in early examples of children’s literature, such as the primer book covered in scribbles or traced letters.

C. S. Lewis, Prince Caspian. New York: McMillan, 1951. Illustrations by Pauline Baynes. Colored by Page Potter, 1960s. Private Collection.

Detail of Palmer Cox Brownies Primer, text by Mary C. Judd, illustrations by Palmer Cox. New York: The Century Company, 1923. Joseph Downs of Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

Coloring books climbed in popularity as the cost of their manufacture decreased. By the early twentieth century, companies selling house paint, shoes, and other consumer goods used coloring books as a marketing strategy. These giveaways allowed them to market their goods either directly to children or to parents through their children. These coloring books were printed on cheap wood pulp paper, and the pages were simply stapled together to form a book.

By the 1920s, the transition to the cheaply made, disposable coloring books we recognize today was complete. The nicely bound books meant to last had been replaced by books that were meant to be used up and tossed aside. These are the coloring books we recognize today, the disposable activity book meant to entertain children briefly before being replaced. The image below is of coloring pages done by the sons of a friend of the author. She keeps coloring pages like these for a month, then scans them and throws them out. It is typical for parent-consumers in the age of disposability to save only a few pieces of their children’s work and the let the remainder go.

Coloring books remain immensely popular. They appear in schools and homes. They are a gender neutral toy, appealing to both boys and girls. They have pictures of favorite characters, magical stories, animals, places, or any number of other subjects. One can even print one’s own photograph as a coloring page. Coloring pages are printed for children of all ages, and now coloring books for adults have become a popular way to relax.

In this project, I explore the history of coloring books as a new form of disposable book, one influenced by changing educational theories and publishing technologies.

“Reading between the Lines” discusses early publications similar to coloring books that helped bring about their creation: children’s magazines, textbooks and primers, and prints of popular images.

“How are the Lines Made?” explores changes in technology in the nineteenth century that made printing images easier and cheaper.

“What Colors?” examines the tools children used on their coloring books, focusing on water colors and later crayons.

“Instructions for the Little Artist” frames coloring books as instructional tools for literacy, art skills and aesthetics, and cultural paradigms before examining a backlash against coloring books in the mid-twentieth century.

“Colorful Characters” studies the way trade catalogues and comic strips built consumer loyalty and brand recognition through coloring books.